So, we had a simple question: when will we be able to catch a robotaxi in Europe? And why can’t we yet? Currently, there are robotaxis (and a small number of roboshuttles) operating in the US, but only roboshuttles in Europe — terms we’ll define later. The difference between the two areas comes down to two things: regulations and ideology. However, let’s take a step back. The first thing to understand is what we mean by autonomous vehicles, robotaxis, and roboshuttles

Levels of Driving Automation

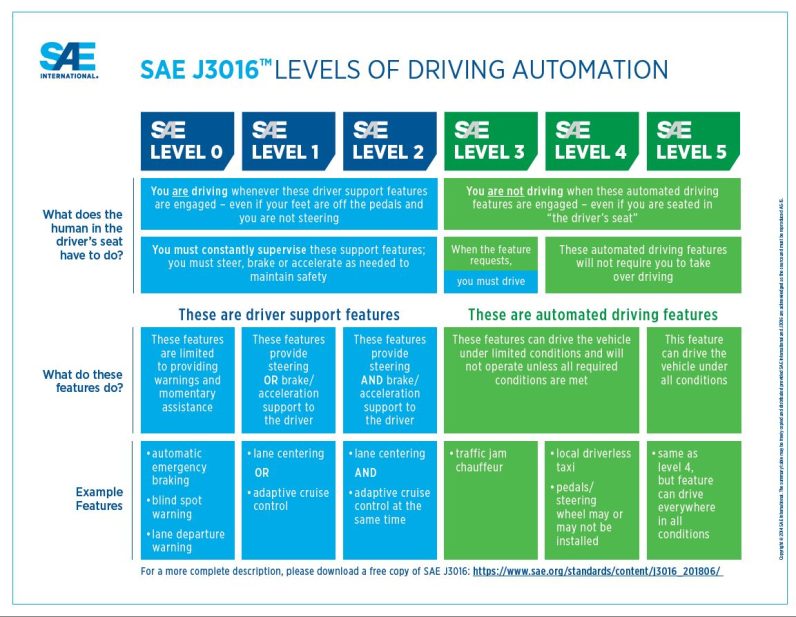

Vehicle automation is far more than the self-driven robotic ride many people imagine. There are five levels of vehicle automation: The investment boom in autonomous vehicles centres around Level 2 to 4 automation. At Level 4, a vehicle can drive itself autonomously under limited conditions. In the future, a Level 5 vehicle will drive itself under all conditions. Currently, there are no such vehicles on the road. Let’s now take a look at the difference between robotaxis and roboshuttles to help us understand why Europe lags behind the US.

Robotaxis vs roboshuttles

When we talk about ride-hail vehicles, there are two kinds of Level 4 autonomous people-carrying vehicles on the roads: Robotaxis, which are designed to carry passengers anywhere in a predefined area, in an urban or suburban environment, and they travel at legal speeds. Roboshuttles (either buses or cars), operate within a predefined route with fixed start and end points and — in the case of the buses — at a far lower speed. To sum it up, robotaxis can take anyone anywhere in a predefined area, while a roboshuttle follows the same route. Now, to understand why we can’t hail a robotaxi in Europe today, we need to understand the current state of the autonomous market.

The state of robovehicles in the EU — this is what you can currently ride

In the EU, it’s all roboshuttle-style vehicles. These vehicles are built from scratch without conventional driving controls, such as a steering wheel or wing mirrors. They operate at a slower speed on commercial and private land, and to a lesser extent, public roads. The biggest player is French company EasyMile, the first to offer a fully driverless L4 autonomous 12-seater shuttles — providing services across business parks, campuses, and public roads. EasyMile operates throughout Europe, being most active in Germany and France. French operator Navya also operates on commercial sites, and in Estonia, TalTech university is running a roboshuttle service on campus as part of a research project. The UK is underwhelming — and limited to several roboshuttle services on commercial land. Industry collaborative body Oxbotica and Sweden’s NEVS aim to deploy vehicles on geo-fenced public roads next year, followed by multiple European projects in 2024. And there’s actually only one operator with plans to offer a taxi service. Last year, Mobileye announced plans to roll out a vehicle in Germany in 2023 in cooperation with car rental company Sixt SE. There’s been no news since. Overall, Europe differs vastly from the US, where multiple robotaxi commercial offerings are active, or in the works. Currently, two companies in the States offer paid taxi-style Level 4 services within predefined areas: GM-owned Cruise and Alphabet-owned Waymo. These vehicles have no driver, and you can book and pay like in a normal taxi. And there are not only plenty of competitors trying to catch up (like Motional, MobilEye, Zoox, and Aurora), but there are also a range of roboshuttle services as well. This brings us back to the initial question: how come the US has robotaxis, and Europe is stuck with roboshuttles? Well, the answer comes back to the very beginning of the article: regulations and ideology.

The US vs EU: Regulation

In the US, passenger vehicles must comply with Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards, but autonomous vehicles are governed at the state level — meaning that states can decide to go all in on the technology. Consider California. It’s already home to the world’s biggest tech companies and investors. This means like Waymo and Cruise can spend years building a relationship with city officials, road safety authorities, advocacy groups, and town planners, giving them a head start. Things are very different in Europe, as the EU requires agreement across multiple countries. To find out more about how this functions, I spoke with Barnaby Simkin from NVIDIA. He leads its regulatory affairs team and is responsible for monitoring and influencing regulations and standards related to AI automation and virtual testing. Simkin shared that the EU has been grappling with the challenge of “giving trust to the industry, giving carmakers the freedom to justify their safety credibility.” But within the Union, countries with a long automotive manufacturing history, such as Germany, are the most motivated to advance vehicle automation. And this seems to be catching on. The EU passed the General Safety Regulation in July. It’s the first legal framework to allow automated and fully driverless cars to become available on European roads.Member states hope its deployment will boost innovation and improve the competitiveness of the bloc’s car industry. Europeans are taking a more methodical, cautious approach, but that doesn’t mean that the collective R&D and cross-industry collaborations aren’t kicking things off. And this is where we get to the ideology part of the argument.

Understanding what lies beneath

There’s another reason for Europe’s delays that goes beyond regulations and explains why we have roboshuttles, not robotaxis. Effectively, the US and Europe have differing views about how automation should fit into the future of mobility. In the US, 45% of people have no access to public transportation. The country is built far more on private vehicles, rather than communal ones — no surprise when you think of the size of it. The figures are still shocking though. In 2021, the US government announced a $108 billion investment into public transport, its largest to date. Sounds huge, right? Well, not so much when you consider that VCs invested $80 billion from 2014 to 2017 in autonomous vehicles — and even more since. Most people ride in private cars, and since investments in public transport are lacking. As a result, cities see autonomous ride-hailing as a way to get people away from car ownership. By comparison, in Europe, operators like EasyMile gain permits to plug public transport service gaps. This year the company launched a service at the Terhills resort in Belgium. Arwid Schmidt, the company’s Director of Strategic Initiatives, Passenger Transportation, told TNW that this project isn’t “a proof of concept.” Nor is it a “demonstration.” Instead, it’s a ten-year deal that replaced a “conventional crewed electric bus on the site,” which wasn’t used enough because they couldn’t get the staff. Now, five EasyMile autonomous shuttles are running the route at a much higher frequency. The company is doing a similar thing in other cities, integrating its shuttles with public transport timetables and ticketing. This contrasts with the US, where most operators (besides May Mobility) prioritize commercially successful routes over filling service gaps. And except forSixt’s announcement (on which we’ve heard nothing since last year), European ride-hailing companies aren’t hurrying to embrace autonomous vehicles. Carlos Herrera, CTO at Spanish ride-hailing company Cabify, told me that the current safety and quality of service is inadequate. He asserts, however, that his company is always happy to consider any solution, “as long as it is in line with improving cities and making them better places to live. But first, the focus must be on reducing emissions to zero now.” At a time of financial uncertainty, these businesses are focusing on meeting their carbon emission targets. This expensive undertaking focuses on replacing ICE fleets withEVs, not investing in autonomous vehicle tech. Again, very unlike the US. And now we can see why Europe doesn’t have robotaxis yet: it has a more robust public transport network, tougher regulatory hoops to jump through, and not as much private investment. But is it really bad that the continent isn’t overflowing with autonomous cars?

Europe’s risk-averse approach to robotaxis has its benefits

The continent’s caution is actually a good thing, as it has managed to avoid the US operators’ challenge of transitioning from trials to a viable business model. In other words, being first means you take the most risks. Recently Ford-owned robotaxi company Argo.ai closed down. In an earnings call, Ford CEO Jim Farley gave some home truths: “We still believe in L4 technology, that it will have an important impact in moving people.” But he also said that creating self-driving “robotaxis” is “harder than putting a man on the moon,” and that “almost $100 billion has been invested in L4″ industry-wide, without a definitive business use case.” And it’s not only Ford questioning the economics. In July, GM said it lost $500 million — more than $5 million a day — on Cruise during the second quarter of 2022. And there’s still a long way to go. Government reporting reveals Cruise has conducted 1,806.8 miles (2907.7 kilometres) of autonomous vehicle journeys with taxi passengers in Q3 of this year. This breaks down to about 20 miles (32 km) a day — half what an average taxi driver could accomplish. This suggests robotaxis are a long way from any semblance of mass deployment, let alone full-scale national operations — and Europe has, so far, sidestepped much of this huge outlay. It will likely continue to do so too, until the long-term wins promised by autonomous vehicle companies come to fruition, and there’s a clear business model. But Europe’s strategy entails danger as well. If the technological capabilities of North American robotaxi companies are so far ahead of Europe, then the continent’s streets will be filled with technology it doesn’t own. The US would effectively be siphoning money off into a different nation’s economy. Still, from everything we’ve seen so far, Europe’s robust public transport network is more likely to merge with autonomous vehicles, rather than be replaced by them. All this leads us back to our original question though…

So WHEN can I ride in a robotaxi in Europe?

I put this question to Christian Gnandt, Vice President of Automated Driving at TÜV SÜD, who thinks robotaxis will arrive “within the next years.” He suggests the most important thing is “not that every single car is driving autonomously in every condition. But it’s really about a specific area under certain assumptions, maybe a certain township of a city and nice weather conditions. This will be the next step.” With all of this to reckon with, Europe’s slower, more cautious approach to autonomous vehicles and their socio-economic implications ultimately puts Europeans in a better position to enjoy what this technology has to offer in the future. We may not have robotaxis yet, but roboshuttles have opened people up to the idea of autonomous vehicles and provided a viable business model. We may not be zipping around in driverless cars any time soon, but, on balance, that’s probably a good thing.