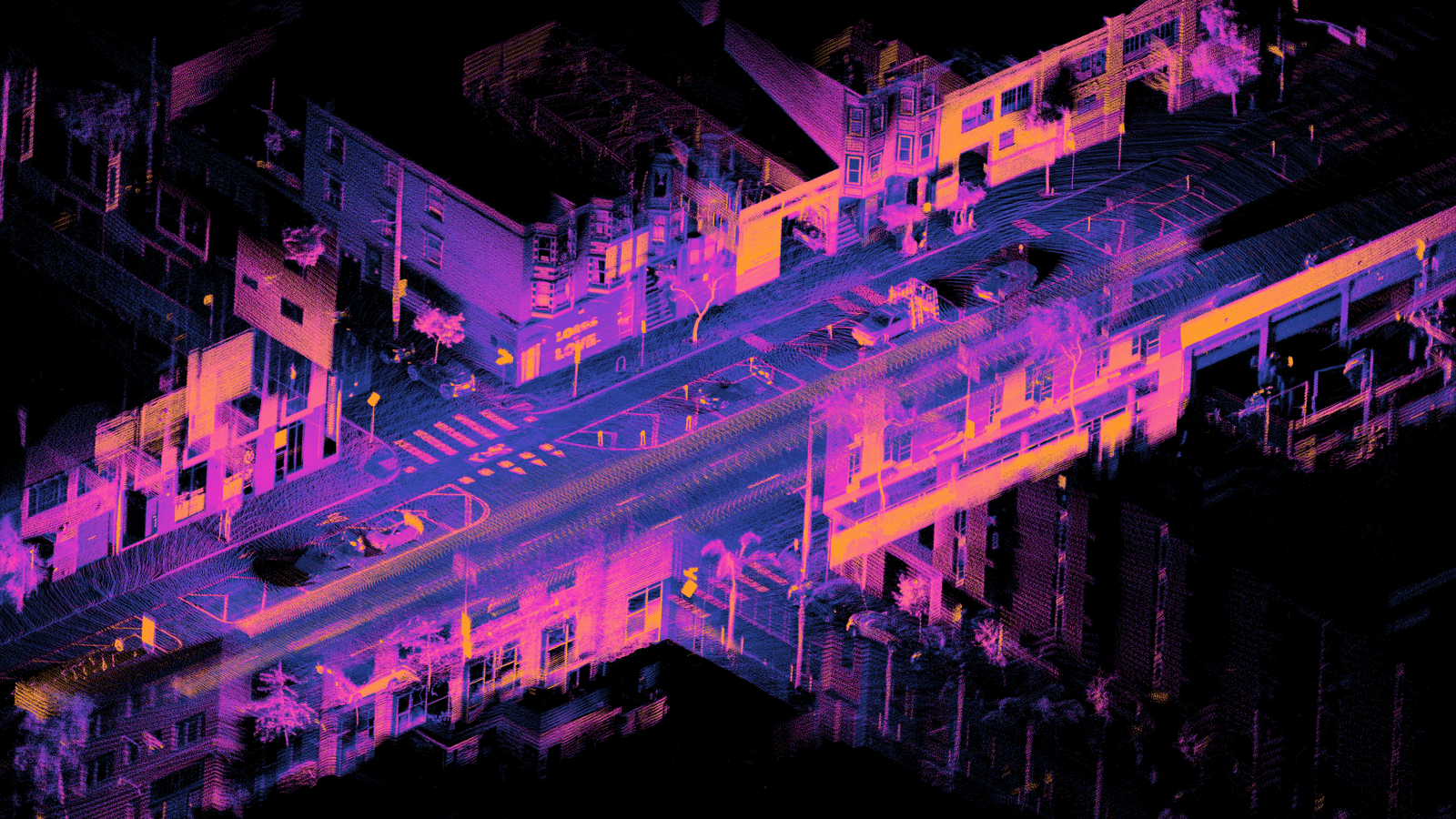

During a case between two of Levandowski’s former employers, Google and Uber, Waymo lawyers allegedly painted the self-driving sensation out to be a troublesome and challenging employee, not the entrepreneurial and passionate engineer his past exploits suggest him to be. But how did Levandowski go from being one of the autonomous driving world’s most promising minds to being fired by Uber and declaring bankruptcy? [Read: Remembering the Nucleon, Ford’s 1958 nuclear-powered concept car that never was] Google and Uber are household names, but Levandowski has only risen to broad public notoriety as a result of various disputes between the two tech giants and himself. So let me fill you in. Anthony Levandowski is a software and technical engineer who is widely acknowledged as being one of the leading names in developing self-driving vehicles. He worked at Google and is credited as being one of the main driving forces behind the company’s division that eventually became spun off into Waymo. He’s a man that always loved a side project, and is universally enthusiastic about developing autonomous technology. During his time at university he led a team that developed a fully autonomous self-driving motorbike dubbed “Ghost Rider.” He and his team entered the bike into a DARPA organized competition, the only two-wheeled vehicle participating. He described it as “the first of its kind, and a frankly crazy idea.” But this crazy idea put him on the map, and made him an interesting proposition for Silicon Valley tech giants. Levandowski’s passions eventually led him to join Google in 2007, to work in its Street View and mapping division. Much of the hardware used in Street View vehicles is very similar to sensors used in autonomous vehicles. In 2017, Google started equipping LiDAR sensors to its Street View vehicles. The company said the technology can help it map the living world in more detail, understand business names, and street signs. The outcome was higher resolution images with fewer stitch errors between individual frames. It helped make using Street View a smoother and more seamless experience. Just weeks after joining the Big G though, he operated and registered his own startup called 510 Systems. For all intents and purposes, 510 Systems was working on similar technologies to what Google was using in its mapping projects. There was substantial overlap between the two companies’ projects — in fact, according to one of 510 Systems’ first hires, Google was the company’s only customer for a year and half. Initially, Google didn’t seem to care much about Levandowski’s side project. If anything, that kind of entrepreneurial spirit is encouraged by it. In typical fashion, the Big G eventually “acquired” 510 Systems in 2011 for some $20 million, according to the Wall Street Journal. If you can’t beat them, buy them? This all went down in 2012, just weeks before Google’s first autonomous driving test on public roads, when someone at the Nevada Department for Motor Vehicles (DMV) found that one of the vehicles registered to be tested was insured, but not owned, by Google. It was listed as being owned by 510 Systems. In other words, Google had to buy 510 Systems to deliver its self-driving car as its own project. But technically, 510 Systems still owned some of the hardware that was presented to the public as being Google’s tech. Whether malicious or simply a by-product of his enthusiasm for the tech, Levandowski, was never one to keep a distinct separation between each of his business lives. Fast-forward to 2016 and Levandowski decided to leave Google to once again indulge his own interests, setting up an autonomous truck company based in San Francisco called Otto. Nearly half of Otto’s initial employees were also from Google.

A suspiciously fast turn around

In just four months, Otto released a third-party kit that could turn a semi-articulated Volvo haulage truck into a vehicle capable of driving itself. Google had been working on self-driving technology since 2009 and it took four years before it completed its first real world test. Otto may have only been adapting ready-made trucks with sensors, cameras, hardware, and software, but four months is a mighty quick turnaround for such advanced technology. Sure, Levandowski himself is clearly an expert on the topic. Even so, many of the technologies he created at 510 Systems and Waymo actually belong to Google, so he should have been starting from scratch at Otto. That turnaround was so impressive that it caught the attention of ride-hailing company Uber, which bought Otto for a reported $680 million in August 2016. [After the debacle that followed, the real figure was confirmed as being closer to $220 million, though.] As part of the buyout, Uber made Levandowski the head of its self-driving division. That four-month turnaround seemingly was too good to be true. In February 2017, Google’s self-driving division Waymo announced that it would be taking legal action against Uber and Levandowski. The Big G claimed that the pair had appropriated trade secrets and intellectual property, and infringed patents. In a statement about the suit, Google said it received an unexpected (and supposedly accidental) email from one of its sensor suppliers. A diagram of what was purported to be one of Uber’s LiDAR circuit boards was attached. It bore a “striking resemblance to Waymo’s unique LiDAR design,” the claim reads. LiDAR, short for: light detection and ranging, is vital to Google’s self-driving technology, and was one of the foundational pieces of hardware that brought Street View to the world. It was certainly suspicious that Uber had designed for such similar technology. In fact, it all sounds like something out of a poorly imagined heist movie. In its statement, Google claimed that six weeks before Levandowski resigned from the company, he downloaded “over 14,000 highly confidential and proprietary design files for Waymo’s various hardware systems, including designs of Waymo’s LiDAR and circuit board.” Levandowski allegedly downloaded all the files to an external hard drive connected to his laptop, and then formatted his computer in an attempt to remove any traces of his alleged nefarious activity. At the time of Google’s lawsuit, Levandowski was employed by Uber who promptly stepped in to begin defending its head of self-driving. The ride-hailing app company denied any wrongdoing, saying that the stolen files never made it to the company’s systems, and set out to contest the allegations. Uber didn’t stick by Levandowski’s side for all that long, but importantly, it never directly denied that he stole the files. In May 2017, a United States District Judge banned Levandowski from working on Uber’s LiDAR tech. Then, by the end of the month, Uber had fired Levandowski for refusing to cooperate with authorities that were investigating the case. Given the drama unfolding, many were expecting a long and arduous legal battle between the two companies of nearly bottomless legal resources. But after just five days, the companies agreed on a settlement of around $245 million. According to a source familiar with the matter, as part of the settlement, Uber was also barred from using Waymo’s hardware and software secrets, The Verge reported. The case was dismissed and, as the judge said, was now part of “ancient history.” But not for Levandowski. In Google’s original lawsuit against Uber, Levandowski wasn’t cited as a defendant. However, given how the case unfolded, and the actions of Levandowski, Google set out another case, this time directly against its former employee. On the whole, the case was largely the same as the one Google had thrown at Uber a few years prior. It indicted Levandowski on 33 counts of theft and attempted theft of trade secrets. Earlier this year, in March, Levandowski pleaded guilty to stealing trade secrets, but only on the provision that 32 of the 33 indictments be dropped. He has agreed to plead guilty to accessing a spreadsheet that tracked Waymo’s projects whilst he worked at Uber. Yet to be sentenced, Levandowski could face up to 30 months in prison for his actions.

Just part of Levandowski’s story

Prior to Google’s original case against Uber, Waymo had taken Levandowski to private arbitration over a contract dispute. Google’s self-driving branch alleged that he “improperly used Waymo’s confidential information to induce Waymo employees to join a competing driverless-car enterprise,” TechCrunch reported. In other words, he tried to poach Google employees to join him at his new job — sound familiar? It should, because a significant number of Otto’s employees were former Googlers. As a result, Levandowski was ordered to pay Google $179 million. At the same time, Levandowski filed for bankruptcy, claiming that he possessed less than $100 million in assets — despite Google once paying him a $120 million bonus. Levandowski isn’t taking the order laying down though. As he was working at Uber at the time the allegations were made, he claims that his employment contract indemnifies him from paying the fine. Levandowski pointed the finger at his former employer saying that it promised to defend him against Google’s lawyers. However, the allegations relate to activities that predate his employment with the ride-sharing company. Uber only came by the trade secrets as a result of its acquisition of Otto. Uber remained quiet on the matter until April 2020, a few weeks after Levandowski pleaded guilty to the original charges, when it said that it wouldn’t front the $179 million bill. The ride-sharing company said that Levandowski’s omission of guilt in March “proved that he is a liar,” Bloomberg reported. Had it known about Levandowski’s nefarious activities, it would never have hired him, the company said. However, Levandowski’s lawyers contest the point effectively saying that Uber was fully aware of who it was hiring. In a due diligence report, prior to hiring Levandowski, the company recognized that he possessed and destroyed “highly confidential Google proprietary information,” according to a Bloomberg report. Levandowski and Uber are yet to publicly resolve their disagreement, and they might never find a resolution for that matter. Given that Levandowski is now bankrupt, and Uber has deep pockets, Levandowski won’t be able to keep fighting much longer. As it stands, it’s Uber pointing the finger at Levandowski, and Levandowski pointing right back. While all this was going on, Uber actually shut down its autonomous trucking business. Back in July 2018, the company announced it was calling time on the project to focus on self-driving cars instead. Knowing what we know now, this decision isn’t surprising. Uber’s acquisition of Levandowski’s Otto caused the company nothing but headaches and financial burden. Uber’s latest attempt to push the $179 million fine back on Levandowski is just the latest example that it wants to distance itself from the now dead project. Since departing from Uber, Levandowski went on to found Pronto.ai, another company that makes autonomous driving tech for trucks. Amid legal proceedings, he stepped down from his role as company CEO in August 2019. The company promised to deliver its first product, called Copilot, in 2019, but according to its website it is still accepting pre-orders. There’s no mention of Levandowski anywhere on the company’s website either. Many have criticized big tech companies for their approach to non-compete clauses and suing employees that go to work for competitors. Critics claim that it stifles innovation, and causes unnecessary stress for employees by barring them from working in their specialist field. Levandowski certainly seems to have been caught foul by this — but he wasn’t just a specialist, he was and still is a leader in his field. There are few who can match his CV when it comes to achievements in self-driving tech. He was hot property for Uber, but it seems he toed the line between what was his own knowledge and what were trade secrets a little too closely. As United States Attorney David Anderson, the judge dealing with Levandowski’s 33-count indictment, said: “All of us have the right to change jobs. None of us has the right to fill our pockets on the way out the door.” While disputes against Levandowski are largely closed cases, something tells me this won’t be the last we hear from him.