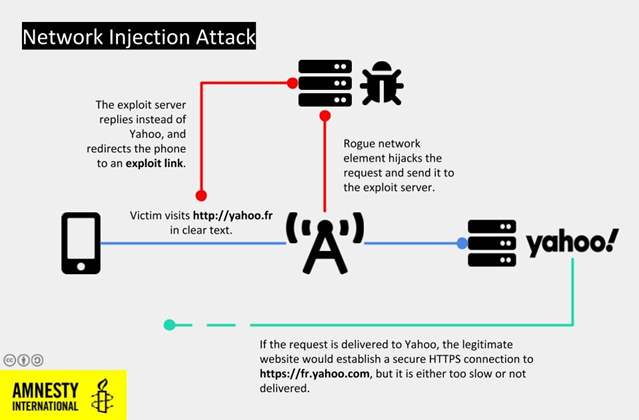

“These were carried out through SMS messages carrying malicious links that, if clicked, would attempt to exploit the mobile device of the victim and install NSO Group’s Pegasus spyware,” the British human rights non-governmental organization said. The report found activist Maâti Monjib and human rights lawyer Abdessadak El Bouchattaoui at the receiving end of a targeted surveillance campaign by hackers with possible ties to the Moroccan government in the wake of Hirak Rif protests in 2016 — a mass movement that’s been met with violent repression and a crackdown on free speech. In addition to delivering malware via booby-trapped messages containing URLs previously tied to NSO Group, the hack — dubbed network injection attack — intercepted the target’s unencrypted web traffic to redirect visits to legitimate websites with pernicious substitutes that infected the devices with spyware. One way this kind of redirection can occur is by employing “a rogue cellular tower placed in the proximity of the target, or other core network infrastructure the mobile operator might have been requested to reconfigure to enable this type of attack,” Amnesty International said. The Israeli company NSO Group is known to sell spyware and hacking tools to governments across the world. The spyware, named Pegasus, features advanced capabilities to jailbreak or root the infected mobile device, and turn on the phone’s microphone and camera, scan emails and messages, and collect all sorts of sensitive information. Back in July, it emerged that the tool had “evolved to capture the much greater trove of information stored beyond the phone in the cloud, such as a full history of a target’s location data, archived messages or photo.” In May, the FT reported a vulnerability in WhatsApp’s audio call feature that allowed attackers to inject iPhones and Android phones with Pegasus surreptitiously. This prompted the Facebook-owned messaging service to issue a server-side update to patch the exploit. Then last week, Google’s Project Zero uncovered evidence of an actively exploited privilege escalation Android zero-day — allegedly said to have been used or sold by the NSO Group — that gave attackers the ability to compromise millions of devices. It’s not fully clear who the targets were in either of those attacks. Although NSO group has maintained that its software is only sold to responsible governments to help foil terrorist attacks and crimes, the latest incident is a reminder that Pegasus has been repeatedly misused to track human rights activists and journalists around the world. “Subjecting peaceful critics and activists who speak out about Morocco’s human rights records to harassment or intimidation through invasive digital surveillance is an appalling violation of their rights to privacy and freedom of expression,” Amnesty International added. NSO Group, for its part, put out a human rights policy in September that aims to “identify, prevent and mitigate the risks of adverse human rights impact.” It also said the tools are not meant to “surveil dissidents or human rights activists” — At this point, the events directly connecting the man-in-the-middle attack to NSO Group are circumstantial at best. But the findings are indicative of sustained attempts by governments and bad actors to spy on activists and journalists. “Instead of attempting to whitewash human rights violations associated with NSO products, the company must urgently put in place more effective due diligence processes to stop its spyware being abused,” the NGO concluded.